Note

seccia.dev version 4.0 January 4, 2026

INTRODUCTIONUnitySoftware InstallationLicenseCompiling the Unity projectPreferencesDocumentationMy games created with seccia.devGAMEPLAYWhat is a video game?What is a narrative adventure game?The four gameplay profilesINTERFACEToolbarNavigation barPROJECTProject settingsConfiguration settingsSavegameCreditsPUZZLENodal boxBest PracticesITEMIconTitleStatePLAYERIconScrolling & ZoomIntegration via codeOBJECTObjectAnimationSub-objectWordsSpecial FeaturesBest PracticesSCENESceneScene PropertiesScene ActionsStage ConditionsEvents on the sceneThe properties of stillStage propScene object propertiesScene Object ActionsThe conditions of the scene objectScene Object EventsLabelLabel propertiesThe label's actionsLabel conditionsLabel EventsShotShot propertiesShot ActionsWallThe properties of the wallGrid & CellCell propertiesCell ActionsCell conditionsCell EventsPath & SpotPath propertiesSpot PropertiesSpot ActionsSpot conditionsSpot EventsDrag & DropDrag and drop eventsTimelineShotsTransitionsSpline InterpolationMusic and subtitlesEventsScene ManagerBest PracticesDIALOGUEDialogueDialog PropertiesActions of the dialogueThe conditions for dialogueThe events of the dialogueRed "Choice" BoxThe properties of choicesThe actions of choicesThe conditions of choiceThe events of choicesBlue Box “Sentence”Properties of replicasConditions for AftershocksThe events of the aftershocksInterfaceStyleThe replicasThe choicesIntegration via codeGAME LOGICLanguagestartupdatetaskgoldrandomscheduleskiprestartendscriptActionsanimatecameracinematicexamineinterpolatejumplightpathplayerpopuplogicselectshowsongstopsuccesstaketalktimelinewaitwalkTermsboolean isdialog hasdialog isobject hasplayer hasplayer ispuzzle isscene hasscene issequence isvalue isEventsFilterson clickon detach itemon drag objecton drop objecton end songon enter dialogOn Enter Stageon exit dialogon exit sceneon inputon reach cellon reach spoton repeaton sayon select labelon select layouton select objecton puzzleon sequenceon switch playeron timelineon unlock choiceon use itemon use labelon use objecton use playeron walkIntegration via codeEFFECTOutputBrightness, Contrast, SaturationBeaconBlurColorizationCurveGrainGrayscaleLook Up TableIntegration by publishersIntegration via codeCINEMATICSVideo, Audio and SubtitlesEncoding an MP4 video fileIntegration via codeAUDIOMusic and soundscapeSound EffectsVoiceBACKUPLocal BackupOnline BackupChaptersShared DataLOCATIONInternal EditingExternal EditingLatin Alphabet, Cyrillic and othersSCRIPTSyntaxVariableBUILDLive, Debug and ReleaseAndroidiOSWebPost-buildCommand lineUNITY PROJECTExposed FunctionsCallbackInterlude

INTRODUCTION

Sylvain Seccia is an independent creator whose unique career spans the worlds of code, image, sound, and storytelling. Trained in software development, he chose early on not to follow the well-trodden paths of salaried employment or mass production. He prefers to experiment, create his own tools, and explore his ideas to their fullest extent, alone if necessary. For him, each project is a handcrafted work, an ecosystem he designs from start to finish with one obsession: to remain true to his vision.

This quest for independence was evident from the early 2000s, when he founded his own development environment in C++. There, he designed engines, libraries, interfaces, and 3D games, often going against the grain of current trends. His philosophy: to build solid, lightweight, and understandable foundations, rather than piling on opaque technological layers. He sees programming as a language in its own right—a means of expression, as precise as a paintbrush or a pen.

But as time went on, technique alone was no longer enough for him. He felt the need to tell stories and convey emotions. This is how, in 2012, Désiré was born, a 2D adventure game that is at once melancholic, tender, and unsettling. Far removed from commercial logic or expected formats, Désiré is a personal, black-and-white narrative inspired by lived experiences, memories, silences, and fragments of imagination. Sylvain wrote the script, composed the music, designed the environments, developed the mechanics… and above all, created the tool that would allow him to bring this world to life: seccia.dev.

Originally conceived as an in-house solution, seccia.dev has become much more than an internal tool: it's a storytelling-centric creation software. A clear interface, accessible scripting, and a logical structure for scenes, dialogues, and triggers—everything is designed to keep the author in control, without getting bogged down in technical details. It's this vision—that of a developer serving the storytelling—that has allowed Désiré to reach a wide audience, with over three million downloads worldwide.

Today, Sylvain continues on his path with the same exacting standards. He continues to develop seccia.dev, not as a purely commercial product, but as a creative partner. He works on new narrative projects, explores hybrid formats, and imagines interactive stories where the technology fades into the background. His driving force is the same as at the beginning: the desire to tell stories differently, to evoke emotion through simplicity, and to remain free.

This book, like seccia.dev, is an invitation to create freely, to reclaim the means of production, and to tell stories without betraying oneself. It's not for seasoned programmers, but for curious storytellers, methodical dreamers, and creators seeking structure to unleash their imagination. If you're looking for a way to code less and tell more, then you've come to the right place.

Unity

Games created with seccia.dev can be deployed on multiple platforms thanks to a runtime developed with Unity. In practice, this involves generating Unity builds from the project included in the software's installation folder.

To simplify this often tedious step, seccia.dev includes an automatic compilation tool for Unity projects, as well as a system for integrating generated builds. This architecture complies with Unity's general terms of use, particularly regarding the requirement for each developer to have their own Unity license.

To enable rapid prototyping and facilitate testing, pre-compiled versions of the runtime are provided for Windows, Android, and WebGL. However, it should be noted that these versions are intended exclusively for development use and must not be used for any final commercial or public distribution.

Software Installation

Before you can take advantage of the software's features, you need to follow a few instructions to ensure that all components are correctly installed.

The software requires:

Windows 11 preferably up to date

A Full HD resolution or higher

And ideally an SSD to optimize frequent disk access.

The Seccia Launcher application installation is available at the following address:

Updates will be available free of charge. You will be notified by a notification that will appear within the Seccia Launcher application interface each time a new version is released.

License

seccia.dev is completely free. No features are deliberately restricted to limit the software's use or hinder its potential. You are free to create, develop, and finalize your games, whether for personal or commercial use, without any imposed technical constraints.

Only certain additional services, such as personalized assistance or supplementary services, may be offered for a fee. For more information, please visit the official website:

Compiling the Unity project

The first step is to download and then install the current version of Unity Hub from the official website:

During installation, ensure you select the modules corresponding to the following platforms: Android (including necessary sub-modules such as SDKs), iOS, WebGL and Windows.

Once Unity is properly installed, launch seccia.dev, open Preferences, select the desired target platforms, and then click the Build selected platforms button to start the build. All you have to do is wait while the builds are generated.

By default, seccia.dev automatically uses the latest version of Unity detected on your machine. However, it is possible to manually specify a path to a particular version in the software's Preferences.

Finally, if you wish to modify the embedded Unity project to add features specific to your game, this is perfectly permitted by the terms of use. However, altering the structure or fundamental properties of the Unity project is strongly discouraged. Such modifications could indeed lead to compilation errors.

Preferences

Preferences are accessible from the main toolbar. If you experience stability issues, you can disable multithreading and GPU acceleration support.

Documentation

All the functions of the seccia.dev language are documented and can be consulted at any time from the software's integrated help page. This central resource is designed to support your progress, whether you are a beginner or an advanced user.

A convenient shortcut allows you to access it instantly: simply position the mouse cursor over the name of a function or keyword in a script, then press the F1 key. The software will then automatically open the corresponding help page, directly linked to the selected item.

This page isn't just about technical documentation. You'll also find links to social media, community content, and regularly updated tutorials. These resources will not only help you deepen your knowledge but also allow you to participate in the growth and dynamism of the community.

Remember to check this page regularly, whether to familiarize yourself with the subtleties of the language or to discover the latest new features available.

My games created with seccia.dev

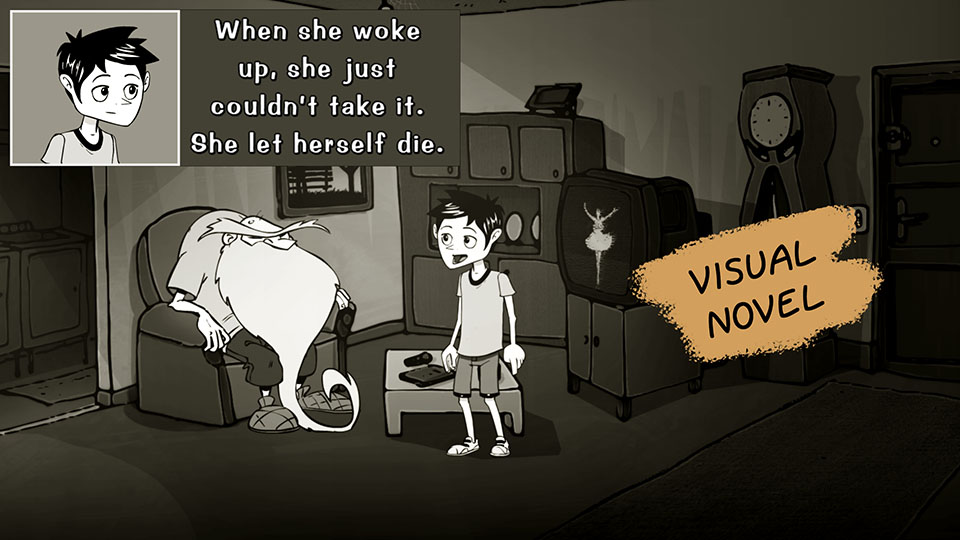

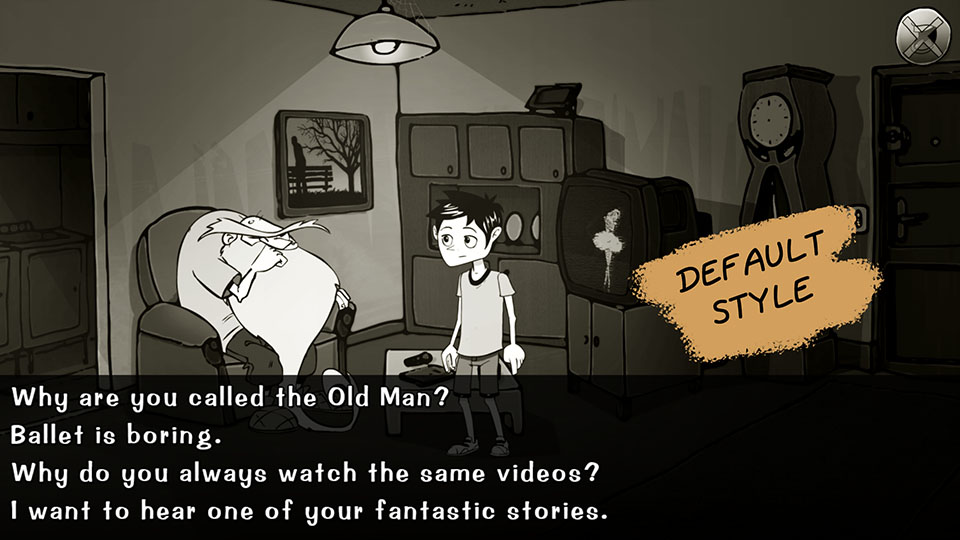

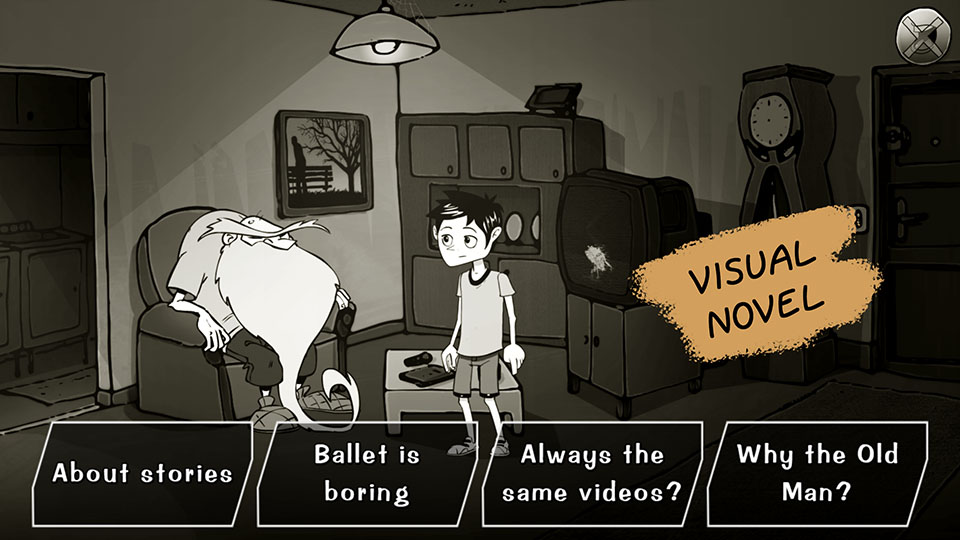

Désiré — 2016

https://www.seccia.com/game#desire

Désiré — 2016

https://www.seccia.com/game#desire

Long Live the King — 2017

https://www.seccia.com/game#viveleroi

Long Live the King — 2017

https://www.seccia.com/game#viveleroi

GAMEPLAY

Before embarking on the creation of your first video game project, it's essential to understand what truly constitutes a game, and even more so, what characterizes a narrative adventure game. Too often, we rush into the visual aspect or the writing of the story without grasping what forms the very backbone of a game: the gameplay. It's the gameplay that defines the rules of the world you create, but also the degree of freedom you give the player. In a narrative adventure game, this structure takes on particular importance, because it doesn't just frame the action: it becomes its language.

What is a video game?

A video game is primarily based on an interactive system centered on gameplay. This term refers to how the player interacts with the game and how the game reacts to their decisions. It's neither pure mechanics nor simple improvisation: it's a balance between structure and expression, between constraint and creativity. It's through gameplay that the player becomes immersed, takes ownership of the virtual world, experiments, and builds their own adventure.

Designing good gameplay requires time, patience, and numerous adjustments. It's not enough to simply imagine appealing features; they must be tested, refined, and balanced. A game can be artistically simple, even rudimentary, and yet captivating if the gameplay works. Conversely, the most beautiful graphics will never save a shallow or flawed gameplay experience.

That said, video games are not just about gameplay. They are also composite art forms, drawing on multiple disciplines: drawing, architecture, music, writing, photography, directing… All these elements enrich the experience, create an atmosphere, and add depth to the game world. But they only serve to flesh out a basic game structure. Without this structure, the work remains inert. The priority, especially at the beginning of a project, must therefore be what makes the interaction come alive: the gameplay.

What is a narrative adventure game?

In a narrative adventure game, gameplay and storytelling are not in competition: they are inseparable. The story is not a backdrop imposed on the mechanics; it is the game's internal logic, its invisible engine. This genre offers a unique form of interaction, where every action is part of an unfolding narrative, every choice resonates within the overall drama.

Contrary to popular belief, gameplay is not secondary. It simply takes a different form. It is not expressed through reflexes or technical challenges, but through observation, dialogue, exploration, and interpretation. The player is not a mere executor: they are an investigator, an active witness, a silent narrator who gradually assembles the pieces of a narrative puzzle.

This type of game therefore demands particular attention to narrative design. If the story is weak, poorly paced, or disconnected from player interaction, the whole thing collapses. The strength of the genre lies in the coherence between narration, presentation, and gameplay. Each element must reinforce the others. In a good narrative adventure game, you don't play alongside the story; you play within the story.

It is this osmosis that gives the genre its richness. More than just entertainment, it becomes a space for interactive expression, an emotional laboratory where the player participates in the creation of meaning.

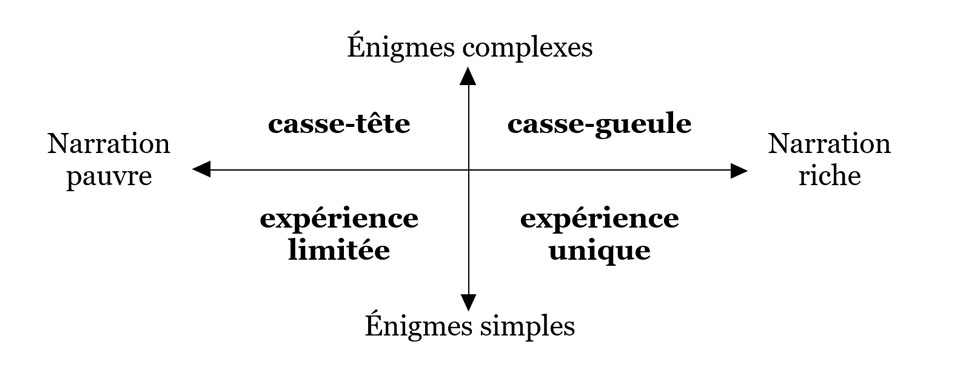

The four gameplay profiles

If the gameplay of an adventure game has two components that we have just mentioned, namely narration and puzzles, then we can propose an illustrated model of four profiles through the following diagram:

Depending on the level of narrative complexity and the density of puzzles you choose to include in your game, you will obtain one of the following four profiles. Each has its own strengths, risks, and implications for the player experience:

| Weak storytelling combined with overly simple puzzles results in a game lacking depth, emotion, or real challenge. Players are likely to quickly lose interest due to a lack of intellectual or emotional stimulation. This type of minimalist experience might be suitable for a tech demo or prototype, but it cannot support an ambitious narrative project. | |

|---|---|

| In this profile, the narrative is reduced to the bare minimum, while the puzzles are numerous and complex. It's no longer really an adventure game, but rather a puzzle game, or an escape room. However, it can be integrated into a larger work: inserting sequences of pure logic within a story can provide contrast and vary the pace, provided they are used judiciously. | |

| This profile combines rich storytelling with complex puzzles. It's arguably the most perilous to master. It demands a delicate balance: each puzzle must be fully justified by the plot and integrate naturally into the staging. Otherwise, the player risks feeling overwhelmed or losing interest, despite the quality of the writing. This type of setup can be relevant occasionally, at key moments in your adventure—to intensify dramatic tension, for example—but it's not recommended to make it the dominant structure. | |

| In my opinion, this is the ideal profile for a successful narrative adventure game. Careful storytelling, combined with simple yet well-designed puzzles, creates a fluid and engaging experience. Simplicity here doesn't mean easy or banal: it's about offering short, understandable, and well-integrated tasks that, taken together, create a stimulating challenge. The player progresses without frustration, while feeling constantly involved. It's these seemingly innocuous micro-puzzles that will lead them to think, observe, and above all, feel, without ever needing to cheat to advance. |

INTERFACE

seccia.dev offers a page-based interface approach, a method uncommon in application development software. In contrast, the window-based, asset-based model is widespread in IDEs, as it is generally practical and efficient in many situations. But is it suitable for all development environments?

For example, in a programming tool, it's inconceivable not to be able to open multiple source files simultaneously while preserving the history of changes. Conversely, in video editing software, working simultaneously on multiple timelines is often unnecessary, or even counterproductive.

Although seccia.dev is more akin to a programming software than a video editing tool, I chose to draw inspiration from the latter when designing its interface. Why? Because this approach, in my opinion, more accurately reflects the production stages of a seccia.dev project. Ultimately, it simplifies and accelerates the creation of your game.

The interface is divided into two parts: the common area and the page area. The common area includes fixed and ever-present elements: the toolbar at the top and the page navigation at the bottom of the window. These shared areas remain accessible at all times and offer functionalities common to several editors. The page area, on the other hand, is dynamic and dedicated to the different stages of the project. It includes tools for managing the scenario, generating executables, accessing educational resources, and accessing the editors. Among these, the scene editor and the role editor will likely be the ones you use most frequently.

The editors are dedicated to the production of assets, that is to say, the creation and modification of essential elements of the game. This includes: objects (including characters), scenes (levels), game logic (graphic code), dialogues (conversations between characters), inventory items, players (control of the main character), cinematics (video in MP4 format) and effects (internal shaders).

Toolbar

The toolbar, located at the top of the window, provides quick access to common software features shared by editors. It is divided into five groups: PROJECT, PUZZLE, PLAY, SEARCH, and IDE.

These icons remain accessible regardless of the page selected, and some are assigned a keyboard shortcut.

| Save the current project |

|---|---|

| Display the project folder in Windows Explorer |

| Create a new asset (shortcut with the Alt key) |

| Access other menus |

| Create a new box for the scenario |

| Crop the view to the selected Puzzle boxes |

| Launch the open scene or a specific scene in Live mode |

| Launch the game in Live mode |

| Launch the game in Release mode for play_web |

| Enable or disable game rendering in editors |

| Enable or disable real-time rendering in editors |

| Access software settings |

Navigation bar

The navigation bar, located at the bottom of the window, allows access to pages and searches within the project.

The pages can also be navigated using a keyboard shortcut.

| Ctrl+Tab | To return to the previously opened page. |

|---|---|

| To access the previous page of the list. | |

| Alt+Right | To go to the next page in the list. |

PROJECT

A seccia.dev project is based on a simple and coherent organization, composed of three main elements:

A central JSON file, which contains all the game data (scenes, objects, scripts, dialogues, etc.)

A binary ASSET file, containing most of the resources (images, sounds, etc.) in an optimized format

External files, placed in specific folders, used for supplementary resources, such as videos or accompanying documents.

This architecture has two major advantages: it simplifies the use of the software for the user, while limiting the risks of corruption or loss of data related to accidental manipulations.

While manually editing JSON or binary files is technically possible, it is strongly discouraged. These files contain unique identifiers that ensure the project's consistency; modifying them carelessly can break these links and cause malfunctions. In other words, you are free to directly edit the files at your own risk, provided you fully understand what you are doing.

Regarding images, seccia.dev exclusively uses the PNG format to store resources in the ASSET file. However, JPEG and BMP formats are also accepted for import: they will be automatically converted to PNG upon integration into the project. Images integrated into a project are automatically processed to optimize the final file size, without compromising visual quality, using the PngQuant library. However, it is important to note that at runtime, all textures are loaded into video memory (VRAM) in an uncompressed format. This ensures consistent display quality but results in higher memory usage.

Project settings

All project parameters are grouped and centralized on the Project page.

| GENERAL | |

|---|---|

| The name of the game, also used to name the files. | |

| The game title. If the field is empty, the title will be the game name. To write in UTF-8, prefix it with @. | |

| Game version in the form of XXX (1.0.0). | |

| Your game package name (com.domain.name) | |

| Developer's name. | |

| Copyright information (Copyright © Year Name) | |

Allows you to define a list of symbols (words separated by spaces) during game generation and to test for the presence of symbols using the code via the symbol function. | |

| GRAPHICS | |

| Only available for mobile devices, this option forces portrait orientation at startup. | |

| Exclusively for desktop platforms, this option forces fullscreen mode when the game starts. In this case, the player will no longer be able to change the resolution in the options. | |

| The game's maximum display dimension is limited to 4096 pixels. This corresponds to the size of the render window, i.e., the area visible on the screen at any given time. However, scenes can have different dimensions, even exceeding this limit. This allows for the creation of large, explorable environments, which will be displayed progressively through automatic scrolling or camera transitions. | |

| When the screen resolution ratio is smaller than your game's resolution ratio, several options are available to compensate for the lost vertical space: | |

| Scroll : The scene height is equal to the screen height and horizontal scrolling is enabled. | |

| Letterbox : Black bars are added to the top and/or bottom. | |

| Crop : The scene is cropped at the top and/or bottom. | |

| When the screen resolution ratio is larger than your game's resolution ratio, several options are available to compensate for the lost horizontal space: | |

| Pillarbox : Black bars are added to the left and/or right. | |

| Crop : The scene is cropped to the left and/or right. | |

| If enabled, Unity will use the FilterMode.Point value. | |

| An effect can be applied to the entire scene. This option is ignored if it is overdefined in the scene editor. | |

| The default size of labels when their value is 0 in the scene editor. If this property is also 0, the system-defined size will be used. | |

| The default color for labels if not specified in the scene editor. | |

| LIGHT | |

| This option optimizes rendering by preprocessing when lighting changes. This pre-rendered image is then stored in a separate texture. The advantage of this method is increasing your game's framerate; the disadvantage is using more graphics resources. If the scene requires constantly changing lighting states, do not enable this option. I recommend using it for static lighting or lighting that changes only occasionally. | |

| This value defines the ambient light of the scene between 0 and 255. If the value is 0, the game screen will be completely black. If the value is 255, the pixels will have their original color. It is not possible to brighten the scene further using this property. | |

| This option applies a blur effect to the light to soften the beam. The higher the value, the greater the impact on performance. | |

| For performance gains, enable this option to reduce the size of textures used for rendering lights. The result will be less detailed and more pixelated. | |

| MENU | |

| This option allows you to customize the interface by specifying the scene that will become the menu's home screen. The jump_menu function will allow navigation from one screen to another within the menu. | |

| An effect can be applied to the native menu. This option does not apply to the custom menu. | |

| The waiting time in seconds. If the value is 0, the player must click or tap the screen to continue. | |

| Display of the Options menu. | |

| Allows you to differentiate between the subtitle language and the audio language. | |

| Displays the menu to change the font size. | |

| Displays the Subtitles menu to change the text scrolling mode and speed. | |

| Allows you to animate menu text with a ripple effect. | |

| Menu color | The color of the menu text. |

| Menu Rate Color | The color of the menu text. Evaluate the game. |

| Menu highlight color | The text color when the player hovers over a menu. |

| Menu value color | The color of the text indicating the option values. |

| The color of the credits text. | |

| The color of the credits text when the line begins with an at symbol (@). | |

| Link that redirects to your web page containing your privacy policy. This link is mandatory if you use online backups. | |

| Link that redirects to your games page. | |

| Customizable button positions. | |

| Customizable menu button size. At 1:1 scale, the size is 96 pixels. | |

| Link that redirects to a web page. | |

| By default, all buttons are visible. To display only the first three buttons, simply type "123". | |

| FONT | |

| The name of the font provided by seccia.dev. It is possible to provide a custom font. | |

| The name of the Asian font used for texture generation. The font must be installed on the computer at the time of generation. If the field is empty or the font could not be loaded, the software will attempt to use a default font. | |

| AUDIO | |

| Allows you to merge the volume of audio sources into a single menu or disable the menu. | |

| Allows you to load all the sounds (WAV files) of your game into memory when the application launches. | |

| Allows you to apply a default dubbing language in case of missing files. If your game is only dubbed in English, you can force the audio for all other subtitled languages. | |

| LANGUAGES | |

| The default language used in the editor. This is usually the native language of the developer or the game. | |

| The default language when the game is first launched. | |

| If this option is enabled, the application will attempt to retrieve the device's language. If this fails, the default language will be used. | |

| Before you can use a language, it is important to activate it to access the fields. When you deactivate a language, the texts are not erased. Use the TEXT/Purge unused languages menu to perform a complete (irreversible) cleanup. | |

| POST-BUILD COMMAND LINES | |

| It is possible to compress all builds at the end of the generation process by enabling this option. |

Configuration settings

You can create build configurations with different parameters depending on the platform and version to be distributed. By default, there are two configurations required for testing within the software: play_windows and play_web. Platforms have their own specific parameters.

| COMMON PARAMETERS | |

|---|---|

| Link that redirects to your games page. If this field is used, the equivalent link in the Menu group is ignored. | |

| Link that redirects to the store page where you can rate the game. | |

| The font size when the application is first launched. If the value is 0, a default value is used. | |

| The size of the cursor in pixels. | |

| The size of the customizable menu buttons. If this field is used, the equivalent link in the Menu group is ignored. | |

| Allows you to include voices, music, and videos. | |

| Command line | It is possible to run a command-line program at the end of the build process. This feature only applies to the Release build. |

| ANDROID-SPECIFIC SETTINGS | |

| Name of the package specific to the configuration. If the field is empty, the package from the Game group is used. | |

| The version of the APK or AAB file as an integer starting with 1. | |

| By default, an APK file is generated. To generate an AAB file for publication on the Google Play store, the option must be enabled. | |

| The Keystore file generated by the Android SDK to sign the APK or AAB file. | |

| The password that was used to generate the file. | |

| The name that was used to generate the file. | |

| The password that was used to generate the file. If both passwords are identical, you must complete both fields. | |

| WEB-SPECIFIC PARAMETERS | |

| Allows you to specify the distribution type. Choose Local to test your game within the software. | |

| Link to the Content folder if the assets are accessible from another location. | |

| Allows you to check the validity of the domain name of the site where the application is hosted. If the option is enabled, a list of authorized domains must be provided. | |

| The list of accepted domain names. The application will not launch if the site hosting the game is not authorized. | |

| Width & Height | The resolution of the game within the web page. |

Savegame

Backup-specific settings:

| GENERAL | |

|---|---|

| Allows you to enable or disable manual backup management. | |

| The version of the game save file. If two versions of the game are too different, it is best to increment this value. Older save files will then no longer be compatible, but this will prevent the application from crashing or obtaining unpredictable results. If the value is 0, save files will never be compatible between two versions. | |

| Allows you to launch an automatic save each time a puzzle box is solved. | |

| SERVER | |

| The link to the folder containing the seccia.dev scripts that allow you to manage online backups via your own website. If the field is empty, the online backup menu will be inaccessible. | |

| Name of the game and therefore of the subfolder to create on your server. | |

| CHAPTERS | |

| The save file in .sav format which will allow a game to be loaded using the load_chapter function. |

Credits

The credits roll at the end of the game and are also visible from the main menu or when calling the show_credits function. Each language has its own text.

The text color is defined by the Credits color property. To change the color of an entire line, simply add the @ character at the beginning of the line. This color can be customized via the Credits title color property.

You can add predefined keywords to retrieve certain properties of your project. seccia.dev provides a list of constants accessible from dialogs, text fields, and variables in your scripts for this purpose.

| The current build platform: Windows, web, Android, iOS | |

|---|---|

| The language selected by the player: French, English, German, Spanish, Italian, Simplified Chinese… | |

| The name of the game without spaces or special characters | |

| The game title | |

| The game version | |

| Developer's name | |

| The Copyright field is filled in the properties |

PUZZLE

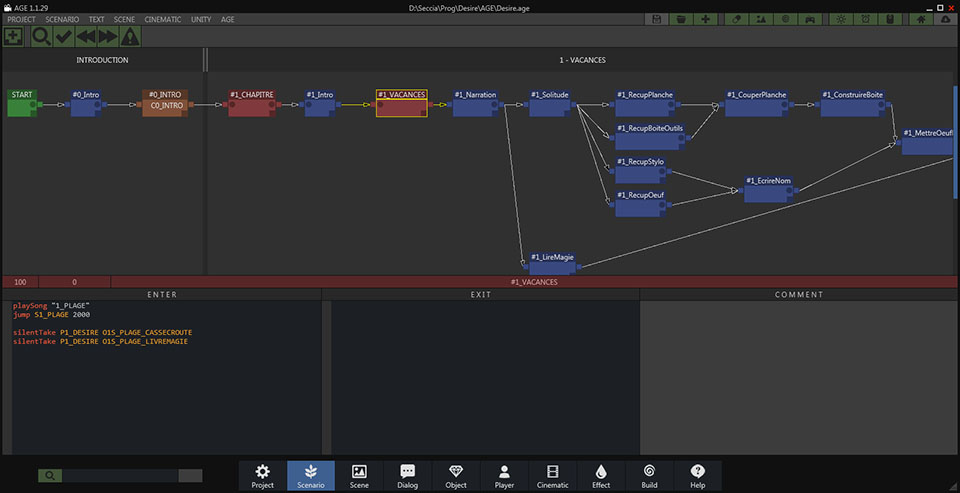

At the heart of the seccia.dev environment lies the puzzle editor. This central tool allows you to define and structure the narrative flow of the game, without resorting to complex programming systems like state machines.

There's no need to manually code the puzzle validation logic: seccia.dev offers a native, simple, and visual solution. You simply add node boxes and then link them together according to the player's progress. During game runtime, a built-in interpreter automatically handles state transitions. The creator's only responsibility is to notify the player that a box has been validated when the corresponding puzzle has been solved.

It's important to clarify, however, that the puzzle editor is an abstract representation of the game's logic. It's primarily designed to organize the narrative, visualize the overall structure of the project, and lay the groundwork clearly and methodically. It doesn't replace the scripts, but rather complements them.

Scripts can only be integrated into role nodes. To view all available language functions, simply click the Help button at the bottom of the main window. There you will find a complete list of commands and their full documentation.

Nodal box

There are five types of node boxes in seccia.dev: puzzle, sequence, or, start, and end. Each fulfills a specific function within the scenario's logic and has properties that are important to understand. To add a box, you can click the [+] button located in the main toolbar to display the list of available types, or use a keyboard shortcut: P, S, O, and E. As you may have noticed, the key corresponds to the first letter of the type. The start box is an exception: it is unique within a scenario.

Puzzle and sequence type boxes must have a name starting with the character #. This prefix is ??used by the engine to identify the active logical points of the scenario.

Puzzle and sequence boxes each have two connectors: one input and one output. The start box, however, has only one output connector, while the end box has only one input connector. The or box has a slightly more complex structure with two input connectors and three output connectors. This may seem confusing at first, but don't worry, we'll go into more detail later.

Each input connector can receive multiple connections, and each output connector can also transmit multiple signals to other boxes. This allows for the construction of branching or conditional scenarios while maintaining clear logic.

Before discussing the logic behind connecting the boxes, it's essential to fully understand the specific characteristics of each of the five types mentioned. It's also important to keep in mind that the scenario progresses in a single direction: from left to right. This corresponds to reading from the past to the future, with no possibility of going back in the narrative structure.

The start and end boxes are mandatory in every scenario. They cannot be completely removed: at least one end box must always remain in the project. When a new game is launched from the game menu, the first box executed is naturally the start box. By definition, no box can precede start, nor follow end.

All end boxes lead to the same outcome: they trigger the credits and permanently end the current game. However, it's important to distinguish between the end of a game and data persistence within the overall game. Some values ??can be retained beyond the current session, allowing information to be maintained between multiple games.

This mechanic opens the door to true replayability: you can, for example, save the endings reached by the player, unlock additional content, or influence new playthroughs based on their previous choices. Thus, although each scenario concludes with an end box, the player's overall progression within your universe can be built over the long term.

The puzzle-box structure is the most frequently used, as it allows you to define the actions expected of the player to advance the scenario. Think of it as a logical loop in which the game remains blocked until the puzzle is solved. As long as the success condition is not met, the scenario cannot progress beyond this box.

The validation of a puzzle box can only be done by the game logic editor via the success action.

The puzzle box, recognizable by its blue color, thus represents a crucial conditional step in the construction of an interactive scenario. It is what makes the player active, by posing a specific expectation to be met before continuing the adventure.

Unlike puzzle boxes, sequence boxes are not blocking. They allow for the automatic chaining of actions or the structuring of the scenario's progression in a fluid way.

Using sequences offers several advantages. They allow for better organization of puzzles, clearly distinguishing their steps and improving the readability of the scenario diagram. This is a good practice for clarifying narrative logic, especially as the project becomes more complex.

Another key advantage of the sequence box is that it automatically defines a logical range around the puzzles it frames. This allows the following functions to be used to query the player's state with respect to this sequence:

| Returns true if the sequence has been started. | |

|---|---|

| Returns true if it has not yet been reached. | |

| Indicates whether the sequence has been fully solved. | |

| Allows you to know if the player is currently within the defined range. |

These functions offer more precise narrative control, particularly useful for triggering conditional events, adapting dialogues, or offering variations based on the player's progress.

if playing #intro// code hereend

It is of course possible to nest ranges defined by sequence boxes, provided that the FIFO (first in, first out) principle is respected. This means that the logical order of entry and exit of the sequences must remain consistent: a sequence started inside another must finish before it can leave the enclosing sequence.

This feature is primarily used to constrain the narrative progression and structure the adventure into clearly defined phases. In theory, the player should not be able to solve a puzzle located outside a beach area until that area is completed. This rule ensures linear or semi-linear progression within a complex scenario.

If this constraint seems too rigid for the type of experience you wish to offer, it probably means that the beach concept is not suited to your narrative needs, and that it would be better to opt for a freer construction, based on independent validations.

Let's take a simple example to illustrate the usefulness of a nested grid: imagine the player falls into an ambush. Until they manage to escape, they are trapped in a closed sequence, limiting their movement and possible actions. This type of situation can be effectively modeled using a sequence enclosing one or more puzzle boxes, ensuring that the player cannot leave this phase until they have completed the required action.

Finally, among the five types of node boxes, the gold box allows the player to be presented with several alternative puzzles, only one of which must be solved to progress. This mechanism introduces a notion of conditional choice, which can produce variations or an impact on the rest of the story.

In this scenario, the player is no longer expected to solve all the puzzles connected to the or box. As soon as one of the puzzles leading to this box is solved, it becomes the selected puzzle, and the others are automatically invalidated. This offers great narrative flexibility for modeling branching paths, sacrifices, or irreversible consequences.

From the editor, it is possible to manually invalidate certain puzzles by marking them as lost. This function is useful for simulating a game state without having to replay everything from the beginning, particularly during testing or adjustments to the scenario's logic.

To use the or box in this configuration, simply connect your puzzles to the first input of the box, then output the signal via the first output. As always with this type of box, the selection condition is set at the input: the first incoming signal determines the outcome. The output is simply the consequence of this choice and introduces no additional conditions.

Keep in mind that the gold box is a valuable tool for structuring non-linear narrative arcs without adding complexity to the graph. Used judiciously, it enhances replayability while simplifying logical construction.

The gold box also allows the narrative to evolve based on the player's choices through the concept of branching storylines. In this mode, it functions as a logic selector, where each input corresponds to a branch of the story and each output reflects that choice.

To implement this, you must use the first two circuits in the box:

The first circuit connects the first input to the first output.

The second circuit connects the second input to the second output.

These two circuits are entirely separate: if a signal enters through one input, it will exit through the output of the same circuit, without passing through the other. The first signal received determines which circuit is selected; all others are ignored or considered lost.

This system is particularly effective for handling two-branch forks, for example a moral choice, an irreversible decision, or a success/failure.

But what about multiple branches, when a scenario requires three or more distinct paths while the gold box only offers two circuits?

It is then sufficient to chain several or boxes together, in cascade, to simulate a system with three or more branches.

That's not all: you've probably noticed the presence of a third output on the or box. This actually represents a third circuit, but unlike the first two, it has no inputs.

This behavior may seem confusing at first, but it follows a simple rule: regardless of the input used, if a cable is connected to this third output, the signal will always be sent to it, in parallel with the selected main circuit. It is not a backup circuit or a catch-up mechanism (therefore, it is not a catch-all), but rather a mandatory supplementary output once it is connected.

In other words, as soon as one of the inputs is activated, the motor sends the signal to two outputs simultaneously: on the one hand to the output corresponding to the input used, and on the other hand to the third output, if it is connected.

This gives you very precise narrative control while maintaining the readability of the graph. This subtle feature further enhances the versatility of the gold box, especially in scenarios with multiple branching paths and delayed consequences.

Except for the special case of the or box, when a box receives multiple incoming connections, its behavior changes slightly. Consider the example of a box #P3 connected to two other boxes #P1 and #P2. The signal will arrive in #P3 when the other two puzzles are solved.

To better understand this logic, imagine that the signal coming from #P1 is waiting at the input of #P3 until the signal from #P2 arrives. Only when all the conditions are met can the scenario progress. This rule guarantees perfect synchronization of converging narrative paths, which is essential for sequences dependent on several previous actions.

Best Practices

Given the potentially large number of puzzles in a game, and therefore the significant number of nodes to integrate into the scenario, adopting a structured naming convention is strongly recommended. A simple and effective method is to prefix each node with the chapter number to which it belongs.

For example, a box named #2_open_gate will clearly indicate that it is an action related to chapter 2, which greatly facilitates navigation in the graph and understanding of the narrative progression.

Even if your game only has one chapter, you can still organize the narrative into acts or logical sequences, using a similar system of prefixes. This allows you to segment the development and avoid getting lost in an overly dense linear structure.

This type of organization isn't mandatory, but rather a best practice. It's up to you to decide, based on the nature and complexity of your story, which method best suits your project. The key is to choose a coherent and readable structure that will effectively guide you throughout the production process.

Regarding assets, the chapter number can also be included in the asset names.

S_HOME, P_HERO, I_KEY, C_INTRO, O_DOOR

The first letter, as we saw earlier, is mandatory and defines its type. A short, precise word is sufficient to describe the asset. If you choose to number the chapters:

S1_HOME, P1_HERO, I1_KEY, C1_INTRO, O1_DOOR

There are generally two types of dialogue in an adventure game:

the conversations, structured and often interactive,

contextual replies, shorter, triggered by a specific action or situation.

To better distinguish and organize them, it is recommended to use a clear nomenclature that includes the name of the character involved or the location where the exchange takes place. This allows you to quickly identify what each dialogue relates to.

D_OLDMAN (dialogue related to the old man)

D_HOUSE (house-specific lines or conversations)

D_HERO (monologues or thoughts of the hero)

For roles, which define the interactive entities in the scene (NPCs, manipulable objects, active scenery elements), the software needs to link each role to a scene so that interactions can be edited and synchronized correctly during the game.

Here again, it is advisable to use the name of the associated scene or player to maintain a clear logic:

R_HOUSE

R_GARDEN

R_HERO

This approach will help you maintain consistency in your asset tree, especially in projects with a large number of files. It also helps avoid duplicates or ambiguities during the scripting or debugging phase.

In terms of puzzles, the titles of node boxes, especially puzzle-type ones, play a crucial role in the readability of the scenario and the efficiency of debugging. A well-structured name allows for quick navigation within complex graphs, the retrieval of a specific action in the blink of an eye, and ensures smoother long-term project maintenance.

I recommend using the following syntax to name your puzzle-type boxes:

chapter_sequence_label

| Indicates which part of the game the puzzle belongs to. This can be a number. | |

|---|---|

| Refers to a situation or phase of the game, such as intro, evasion, chase, combat, negotiation, etc. This word must be unique within its chapter. | |

| Specifies the context or action of the puzzle. This can refer to an event, an interaction, or a location. |

When the puzzle involves an interaction between several objects, it can be helpful to add a note to the box (comment area) to document this relationship. Use the following syntax for clarity:

I_KEY + O_DOOR or I_WATER + I_BOTTLE = I_FULLBOTTLE

These notes have no impact on execution, but they constitute valuable documentation for you, your collaborators, or anyone who may take over the project.

It is important to consistently implement sequence ranges in your scenario so that you can accurately track the player's progress using associated functions such as started, ended, playing, or unstarted. These functions are even more effective when the scenario structure is well-segmented.

To maintain clear consistency and make the graph easier to read, remember to use the sequence name in each puzzle it contains. This strengthens the project's organization and allows for the logical grouping of actions related to the same narrative moment.

A handy tool accessible via the context menu lets you rename multiple boxes simultaneously after selecting them. This saves you valuable time, especially during the script review or harmonization phase.

Furthermore, you can use the sequence box body (the internal text field) to indicate the emotional mood associated with the current sequence. To do this, it is recommended to first define a list of emotions or moods specific to your game, such as: love, joy, sadness, fear, anger, shame, intrigue…

This purely descriptive annotation is invaluable to artists, and especially to the composer, who can thus better grasp the narrative intent and overall atmosphere of each moment in the game. This type of information strengthens the overall artistic coherence, while also facilitating collaboration between the narrative, sound, and visual departments.

ITEM

In an adventure game, items are central to the gameplay experience. Players collect, examine, combine, and use them to progress through the story. They represent one of the primary forms of interaction in this genre, and their design deserves careful attention. This is where your project's item editor comes in.

An item is a virtual object placed in the player's inventory. It can be a key, a journal, a clue, an ingredient, a broken object, or a mysterious tool. Each item holds a gameplay promise: it triggers an action, a thought process, or an interaction. The item editor allows you to create these objects, configure them, and define their appearance in the game.

The item editor doesn't just dress up a game; it structures its gameplay. It's through these items that the player tests their hypotheses, tries out combinations, and overcomes obstacles. Each item must therefore be designed in relation to the mechanics you've implemented: where to find it, what it's used for, how it evolves, and when it should be used.

For example :

A rusty key will be able to open a specific door if it has been cleaned with another item.

An old book can reveal important information if the player has read it in the right context.

A precious stone can be placed in a sculpture to trigger a hidden mechanism.

The editor gives you all the flexibility needed to manage these interactions, whether through a system of scripts, conditions or combinations between items.

Icon

Each item can have a maximum of four icons, numbered from 0 to 3. These icons are used to visually represent the object in the user interface, particularly within the inventory bar.

The default icon, essential for displaying the object's purpose, always has the number 0. It must be present if you want the item to appear in the interface.

The following function allows you to dynamically change the icon currently in use:

xxxxxxxxxxset_item_icon I_KEY 1

The optimal icon size is 256×256 pixels, in 32 bits (with alpha channel). To preserve performance, an icon's texture is only loaded into GPU memory if it is actually displayed in the inventory bar.

Title

This is the item's name, as it will appear on screen when the player hovers over it, selects it, or interacts with it. It should be clear, evocative, and sometimes intentionally enigmatic if the gameplay warrants it.

The pipe separator | allows you to define multiple titles for the same item. By default, only the first title in the list will be active, but using the set_item_title function, you can choose another title by specifying its index starting with 0.

State

In an adventure game, a single item can change state as the player progresses. Rather than creating multiple separate items for each variation, the software allows you to assign multiple titles and icons to a single item. This feature offers great flexibility and significantly simplifies inventory management.

An object can thus evolve without losing its identity. For example:

An empty bottle becomes a full bottle after being filled at a fountain.

A closed can becomes an open can after being used with a can opener.

In a more whimsical vein, a crumpled document becomes a readable document after being ironed or slightly moistened.

These changes are not merely visual: they reflect a transformation in the game's logic. The player understands visually and textually that the object's function has changed, which can unlock new interactions or dialogues.

I know what you're thinking: creating a new item for each state might seem tempting, but it unnecessarily burdens the project structure and complicates the management of conditions, interactions, and dialogues. Using the same item with variable states maintains internal consistency while reducing the risk of errors (duplicate items, cluttered inventory, redundant scripts, etc.).

In summary:

The title reflects the role or state of the object at a given moment.

The icon shows its current appearance.

A change in one state often implies an update of both.

Here is an example:

xxxxxxxxxxset_item_icon O_BOTTLE 1set_item_title O_BOTTLE 1

This approach enhances player immersion while providing you with a powerful tool for designing fluid and consistent puzzles.

PLAYER

The player editor is a fundamental tool in the construction of an adventure game. It defines what it means to "be the player" in your interactive world. Specifically, it relies on two major components:

The 3Cs

The inventory of items

The editor's primary role is to configure your Player asset, that is, the set of elements that govern the 3Cs:

| This is the character displayed on screen, which must reference an asset of type Object. This object can also be modified by code. | |

|---|---|

| Refers to the interactions between the player and the character, primarily managed by the engine. | |

| The camera is associated with the active player. It can be configured from the editor, giving you control over framing, zoom, and behavior during movement. |

These three elements form the basis of the embodiment experience. A balanced configuration of the 3Cs is essential to guarantee an intuitive and immersive experience.

The second role of the player editor is the inventory, that is, the list of objects that the player can collect, examine, combine, or use. This inventory is directly linked to the game mechanics: it is an interactive space where the player's choices materialize.

Each item in the inventory comes from the item editor we saw in the previous chapter, and its use depends on the narrative or logical context you have defined. It is in this interface that you manage what the player possesses to interact with the world around them.

It is entirely possible to design a game with multiple inventories, associating each inventory with a distinct player. You can then dynamically switch players via code or through interactions within the game interface, allowing you to vary perspectives or mechanics depending on the narrative sequences.

Icon

As with items, each player can have a maximum of four icons, numbered from 0 to 3. These icons are used to visually represent the character in the user interface, particularly within the inventory bar.

The default icon, essential for displaying the character's portrait, always has the number 0. It must be present if you want the character's face to appear in the interface.

The following function allows you to dynamically change the icon currently in use:

xxxxxxxxxxset_player_icon P_HERO 1

However, if your game does not offer the option to switch between multiple playable characters, the icons become optional and can be ignored without consequence.

The optimal icon size is 256×256 pixels, in 32 bits (with alpha channel). To preserve performance, an icon's texture is only loaded into GPU memory if it is actually displayed in the inventory bar.

Scrolling & Zoom

seccia.dev offers a set of simple but powerful tools to control camera behavior, directly related to the character's position on the screen.

Automatic horizontal scrolling of the scene can be enabled or disabled at any time. This is done either by checking the Scrolling box in the editor, or via script using the enable_scrolling and disable_scrolling functions.

For smoother gameplay, you can enable a smooth scrolling effect, which applies a gradual deceleration rather than an abrupt stop when the character stops moving. This significantly improves visual comfort, especially in more cinematic scenes.

The camera zoom can also be enabled or disabled dynamically, by checking the Zoom box or via the enable_zoom and disable_zoom functions.

In addition, seccia.dev offers other features to enhance the staging by manipulating camera movements. For example:

| Applies a temporary camera shake (ideal for simulating an impact, earthquake, etc.) | |

|---|---|

| Generates a fluid ripple effect to create an unstable or unreal atmosphere. |

All of these functions are documented in detail on the help page accessible from the software interface.

Integration via code

Managing players in scripting is simple. Since a player represents a playable entity, to assign them a character (object) to control, use the control function. A player can only control one object at a time. The inventory remains associated with the player, regardless of the object being controlled.

xxxxxxxxxxcontrol P_HERO OC_HERO

To indicate which player is currently active, use the switch function. Only one player can be active at a time.

xxxxxxxxxxswitch P_HERO

If the game has multiple playable players (character switching mid-story, alternating co-op, etc.), you must specify the list of players visible in the inventory bar. Note: the active player is never displayed in this list.

xxxxxxxxxxset_player_list P_HERO P_FRIEND

Each player must be linked to a starting scene, even if they are not yet active. This allows the engine to know where to locate each player from the start of the game.

xxxxxxxxxxset_player_scene P_HERO S_HOUSE

OBJECT

The object editor allows you to create objects in the broadest sense of the term and configure them before instantiating them in scenes. The generic term "object" is therefore used to refer to active objects, static objects in the scene, and game characters.

Objects cannot be added directly to the player's inventory; you must use items. If you need to retrieve a key in a scene in the form of an object, you will need the equivalent in the form of an item.

The first column of the interface lists the three default animations STOP, WALK, and TALK, even if they are empty, and just below them the names of your own animations. Each animation has its own parameters.

The second column lists the properties of the object, animations, and sub-objects by category.

The third column is reserved for viewing the selected frame.

The frames of the selected animation are displayed at the bottom of the editor.

Object

In the second column, reserved for properties, you will find the exhaustive list of parameters relating to the object, detailed in the following table:

| ID | |

|---|---|

| You can define up to four tags per object. They allow you to identify objects by something other than their name in order to group them by category. A fifth tag can be modified using the set_asset_tag function. | |

| The title is displayed on the screen when the player interacts with the object. For example, when the mouse cursor hovers over the object's interaction area. If the field is empty, interaction will be limited to selections. The separator pipe | allows you to define multiple titles for the same object. By default, only the first title in the list will be active, but using the set_title function, you can choose another title by specifying its index starting with 0. | |

| The description provides information about the item for the creator. | |

| MOVEMENT | |

| Anchor X/Y | This point, marked with a red cross, is used to manage the scene's depth, that is, the order in which objects are displayed. Because the scene is only two-dimensional, the Y coordinate is interpreted as a Z coordinate: the smaller this value, the farther the object will be from the camera. This point represents the object's base in contact with the ground or a support. For example, for a character, this would be the feet, while for a statue, it would be the base. If the object is placed on a table, another property in the scene defines the object's height relative to the ground. This scenario is only relevant if the character needs to move both behind and in front of the statue. The values ??are in pixels and relative to the original image. You can either enter the values ??or double-click on the preview. Finally, if your object is supposed to change direction, the X position must absolutely be in the center of the image to avoid a transition misalignment. I therefore advise you to center your characters at the spine and adjust as needed by testing. The set_anchor function allows you to change the values ??code-wise. Rotations also rely on this point to define the center. |

| This is the walking speed in pixels per second. Note that these values ??can be overridden in the scene editor if your perspectives differ between two scenes. | |

| When the player clicks on a part of your environment, the character automatically moves to that point, taking the shortest path with the fewest possible changes of direction. If the destination is too close to the character's current position, the movement will be perceived as a quick jump where the walking animation is abruptly interrupted. To avoid this unpleasant graphical effect, simply define the minimum allowed distance in number of cells to trigger movement. This constraint is ignored when the player interacts with an element. | |

| SPEAKING | |

| If your object is capable of speaking, you can customize the color of the dialogue using a list of 16 predefined colors. The RGB value of each color can be modified from the project page if it is not suitable. | |

| Customize the style of the choices for your dialogues. These styles can be configured on the project page. | |

| Customize the style of the dialogue lines. These styles can be configured on the project page. | |

| To display the photograph or avatar of the speaking character, you must select an object from the list and choose the Visual Novel style. The TALK animation plays when the character continues speaking, and the STOP animation plays when the player is prompted to choose a response. The STOP animation is used instead of the TALK animation if the latter is absent. If the STOP animation does not contain any images, no avatar is displayed at the time of the choice. | |

| INTERACTION | |

| This option disables possible interactions with the object. You can change this value in scripts using the enable and disable functions. If your object doesn't have a title, it's best to disable interactions to avoid incomplete sentence structures. | |

| By default, the active area of ??the object is defined by a rectangle, aligned on the X/Y axes and encompassing all the pixels of the current frame. This rectangle can therefore be different in size from the image. By disabling this option, you will obtain greater precision based on pixel detection of your images. Of course, this precision comes at a significant cost for high resolutions and animated objects. I advise you to enable it only when absolutely necessary. | |

| This option allows you to disable possible interactions with sub-objects. You can modify this value from within scripts using the enable_subs and disable_subs functions. If your sub-object does not have a title, it is best to disable interactions. | |

| OPTIMIZATION | |

| seccia.dev generates texture atlases to limit the number of textures the graphics card loads at runtime. A texture atlas is composed of several images separated by two transparent pixels to optimize loading time. Furthermore, the sizes, expressed in pixels, are variable to save graphics memory. It's better to have three textures of 512x512 than a single texture of 1024x1024 to save 262,144 pixels. The maximum size of the texture atlas is adjustable. By default, the value is 2048. If your images are larger than the maximum size, they will be resized, resulting in a loss of quality. |

Animation

Each object in seccia.dev can contain predefined animations as well as custom animations:

Three default animations are reserved for internal engine actions (STOP, WALK and TALK).

You can add as many additional animations as necessary to enrich the visual behavior of the object.

An animation is composed of several directions, each containing its own frames (successive images). This structure allows for the precise definition of an object's appearance and movement according to its orientation in space.

The four primary directions are RIGHT, LEFT, FRONT, and BACK. The four secondary directions are FL (front left), FR (front right), BL (back left), and BR (back right). Secondary directions are useful if you want to move in eight directions. If your object only has one direction, it is recommended to use RIGHT by convention. No direction is mandatory: you are free to define only those that are useful to your game.

Each direction can contain up to 250 frames, indexed from 0 to 249. This gives you great freedom in animation while ensuring controlled performance.

| MANAGEMENT | |

|---|---|

| The LEFT, BL, and FL directions can be determined by the RIGHT, BR, and FR directions by applying a mirror effect if the option is enabled. The primary advantage is to limit the size and number of textures to be generated. | |

| By default, there is no transition when the character changes direction. To add one, you must specify the target animation in this field for each transition. For example, if you want to create a transition from LEFT to RIGHT: you must first create a new TURN_LEFT animation (name of your choice) with RIGHT direction frames where the character will turn from right to left, and then you will choose the LEFT option. In the other direction, it's the same principle by adding LEFT direction frames to the TURN_RIGHT animation (name of your choice). | |

| FRAMES | |

| The number of frames per second. | |

| By default, an event is called at the end of an animation, that is, either at the index of the last frame or at index -1. In some situations, for example for a TAKE animation, triggering the event would be more appropriate at the moment the object is picked up. | |

| Loop count | The animation can be played once or multiple times in a loop. Specify -1 for an infinite loop. For the three main animations, the loop is always infinite. |

| You can create a subloop by defining the initial and final frames. Specify -1 to use the last frame of the animation. | |

| Range loop count | The number of loops in the range defined previously. |

| The profile allows you to change speech characteristics. For more information, refer to the Speech section of this chapter. | |

| OPTIMIZATION | |

| It is very important to group texture atlases according to the use of animations. If you have an animation that only plays once in the game, it is not necessarily needed to keep it permanently in memory. There are different ways to do this depending on the usage. Loaded with object: By default, the animation is loaded with the object when it is present in a scene. This is the default mode without optimization. Loaded only for scene: The animation is loaded into memory only when the specified scene is opened. This is unnecessary if the object is in only one scene. Loaded on the fly: The animation is fully loaded just before it appears on the screen, then unloaded at the end of playback. A slight delay may be noticeable if the animation is large, and even more so if the graphics card is not very powerful. Streaming: The animation is loaded frame by frame, like a video. This mode should be tested on lower-end systems to ensure that the animation's frame rate can be guaranteed for your players. |

Sub-object

Sub-objects are rectangular interactive areas defined within a main object. They allow you to create several independently named, clickable parts within the same object. This is particularly useful when you want to, for example, distinguish different parts of a character's body (such as a hat, a cane, or a bag) without having to create new, separate objects.

A sub-object should not be confused with a rectangular portion. Sub-objects are only used to declare elements that inherit from your object. You must then define the clickable rectangle on all necessary frames. Pixel-level collision detection is also applied to sub-objects.

After creating and selecting a sub-object, new properties are displayed in two new sections: Frame and Sub-object.

Regarding first the identity of the selected sub-object:

| ID | |

|---|---|

| The name of the sub-object. A color will be automatically assigned to it in the editor to differentiate the rectangles. | |

| This is the title of the sub-object. If the field is empty, interaction will be limited to selections. |

Regarding the properties of the selected frame:

| INTERACTION | |

|---|---|

| The coordinates of the rectangle. Another way to define the rectangle is to select the portion of the image by holding down the left mouse button. You can use the popup menu to copy the current coordinates to memory so you can quickly apply them to other frames. |

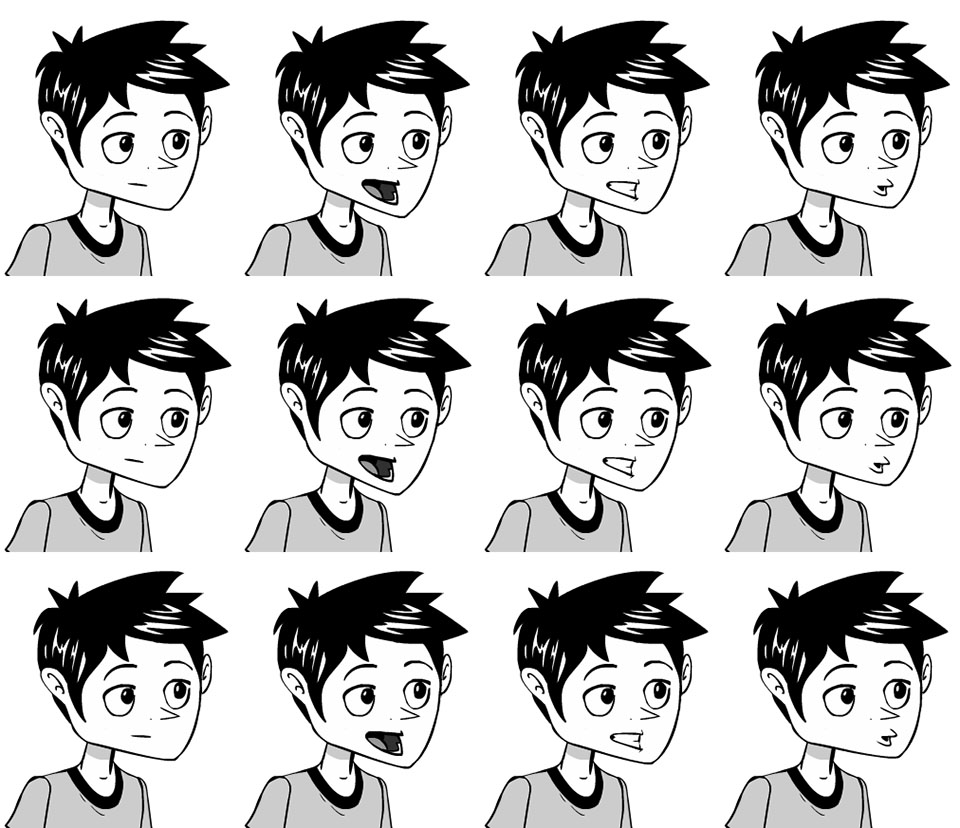

Words

You must provide three head tilts so that seccia.dev can randomly select frames, applying constraints based on the selected profile. Good to know: the algorithm will never randomly select the same image twice in a row.

The tilts must contain identical facial poses. If your animation has four poses, then you will need twelve frames in total (i.e., 4 poses x 3 tilts) as shown in the example below.

The images are numbered from 0 to 11 from left to right and top to bottom. The first line corresponds to the normal head tilt. The second to a downward tilt, and the third to an upward tilt. Note that the tilts should be barely perceptible for a natural look.

Special Features

The functions accessible from scripts do not allow modification of an object's properties. Unlike other assets, the object is not instantiated when the game starts, as it is primarily a graphical model used to construct entities. Therefore, an object can only exist through one or more instances created within scenes.

When an object is placed in a scene, it becomes a scene object, since its characteristics then depend on the scene's context. It is therefore important to distinguish between the concept of an object (the model) and that of a scene object (the instance), because the same object can give rise to as many scene objects as there are scenes that use it. Thus, changing the title of a scene object will only affect the instance in question.

The functions listed in the Play section of the help page are reserved for the states of the current scene.

Best Practices

It is important to name animations correctly by classifying them by location or action to prepare for game memory optimization and minimize refactoring, which will negatively impact your deadlines.

If an animation is specific to a scene and the object appears in multiple locations, you can choose one of these three optimization modes.

| Only for scene | Advantage : No latency when playing the animation.

Disadvantage : Textures load when the scene opens, even if the animation is not playing. |

| ------------------ | ------------------------------------------------------------ |

| On the fly | Advantage : Fewer textures to load if the animation is not playing.

Disadvantage : Significant latency before the animation plays due to the loading of all the frames. |

| Streaming | Advantage : Fewer textures to load (frame by frame) and very little latency before the animation plays.

Disadvantage : On some low-performance hardware configurations, the animation may slow down and not play at the correct speed, especially if the animation speed is high. |

As a general rule, it is better to stream large and non-recurring animations.

seccia.dev is clever; it can avoid unloading an item if that item is also present in the next scene being loaded. Therefore, if your main character is in every scene, their resources will never be unloaded during the game.

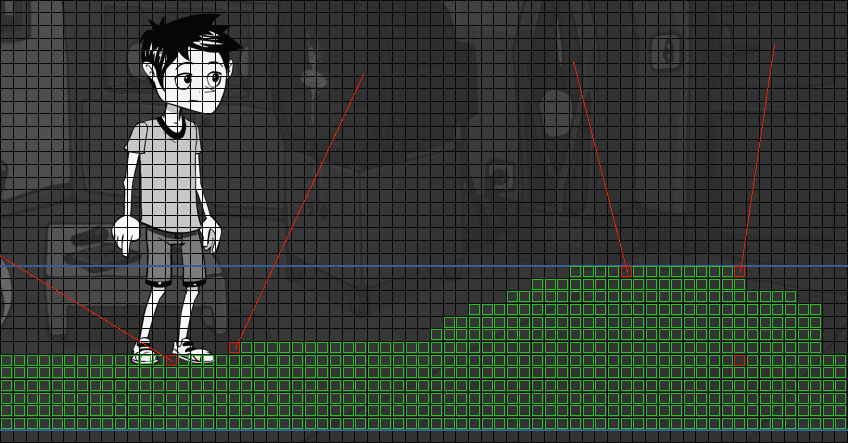

SCENE

The scene editor lets you compose your game's levels by placing objects, configuring interactions, and orchestrating the visual and narrative elements that make up your adventure's world. You'll likely spend most of your development time on it.

One of the great strengths of seccia.dev lies in the simplicity with which you can define the character's movement area (walking range), while associating actions with complex behaviors, without having to write a single line of code. For example, when a player clicks on an object to pick up in the environment, the engine can automatically move the character to the object and then trigger a contextual animation (such as crouching or reaching out). This logical sequence is managed visually using grids and cells, tools that we will detail in a dedicated section.

The scene editor also allows you to design in-game cinematics without leaving your workspace. To do this, you can use timelines and insert shots (shot values) to control the camera, movements, dialogue, and synchronized actions.

Scene

A scene in seccia.dev consists of several visual and interactive elements, organized to create a rich and vibrant environment. It includes:

a main setting,

foreground or background layers,

stills (fixed or decorative elements),

interactive objects,

and clickable areas defining possible interactions.

When you create a new Scene asset, the first step is to replace the default background with an image of your choice. This image must be in PNG format to support transparency.

Right-click the Back icon in the Scene toolbar, then select a file to import. Once imported, the image becomes the main background of your scene and serves as the basis for arranging objects, layers, and interactions. The image dimensions define the scene size and, consequently, the number of grid cells. If the scene size differs from the game's resolution, black bars will be overlaid or horizontal scrolling will be applied, depending on the project settings. The cell size is fixed at 16x16 pixels regardless of the game's resolution.

There are two types of layers: backgrounds (FAR) and masks. You can add a maximum of four backgrounds and four masks per scene. The display order of the nine images, including the main background, is as follows, from foreground to background.

| Mask A is displayed in the foreground (closest to the camera). | |

|---|---|

| Mask B is hidden by mask A. | |

| Mask C is hidden by mask B. | |

| The D mask is hidden by the C mask. | |

| The main set, hidden by the masks, defines the size of the stage. | |

| The first distant setting. | |

| The second distant setting. | |

| The third distant setting. | |

| The set furthest from the camera. |

If the main background is completely opaque, distant backgrounds will not be visible. Layers can be enabled or disabled via code by adding crossfade effects.

For performance and graphics compatibility reasons, seccia.dev automatically splits layers when they exceed certain sizes. Images are transformed into textures with dimensions that are powers of two (512, 1024, 2048, etc.), in accordance with modern graphics card standards. This process ensures better memory efficiency and faster data access. This splitting is transparent to the user: the on-screen rendering remains smooth and accurate, regardless of the internal texture splitting.

Scene Properties

When no element is selected, you can access the scene properties in the list located at the top right of the editor.

| SCENE | |

|---|---|

| You can define up to four tags per scene. They allow you to identify scenes by something other than their name in order to group them by category. A fifth tag can be modified using the set_asset_tag function. | |

| An effect can be applied to the entire scene. If the property is empty, the scene will use the Effect field of the project. | |

| LIGHT | |

| Baked lights | Allows you to override the property defined in the project properties. |

| Allows you to override the property defined in the project properties. -1 uses the project value. | |

| Allows you to override the property defined in the project properties. -1 uses the project value. | |

| Allows you to override the property defined in the project properties. | |

| BACKGROUND | |

| Changes the visibility of the scenery in the editor. | |

| Changes the layer's blending mode. | |

| Default : Transparency simulation uses RGB values ??premultiplied by the alpha value. | |

| Addition : Colors are added together to produce the final rendering. Black pixels will become transparent. | |

| Defines the percentage of opacity used to produce a transition effect between two values. | |

| Defines the speed multiplier of the transition. At 100%, the factor is equal to 1. | |

| Intercepts the player's click if the pixel is opaque. | |

| MASK | |

| Changes the visibility of the scenery in the game. | |

| Changes the visibility of the scenery in the editor. | |

| Changes the layer's blending mode. | |

| Default : Transparency simulation uses RGB values ??premultiplied by the alpha value. | |

| Addition : Colors are added together to produce the final rendering. Black pixels will become transparent. | |

| Applies a horizontal and/or vertical repetition of the image to fill the empty space. | |

| Offset X/Y | Shifts the image horizontally and/or vertically in pixels. |

| Changes the horizontal scrolling speed of the scene. At 100% the mask scrolls as fast as the main background, at 50% it scrolls half as fast, at 200% it scrolls twice as fast, and at 0% the speed is adjusted according to the size of the main background and the mask. | |

| This refers to depth parallax. To create an illusion of depth when the character moves away from the camera, it is necessary to increase the magnification of the foreground layers relative to the background. By default, all layers have the same magnification factor. | |

| Defines the percentage of opacity used to produce a transition effect between two values. | |

| Defines the speed multiplier of the transition. At 100%, the factor is equal to 1. | |

| Intercepts the player's click if the pixel is opaque. | |

| FAR BACKGROUND | |

| Changes the visibility of the scenery in the game. | |